As a preservation carpenter and traditional joiner I spend a lot of time trying to retrace the steps of early craftsmen. While the fruits of their labors survive in pockets — the buildings and pieces that survive; the places where they worked and plied their trades often did not. Thus we often have to look for tool marks, log books, letters and newspapers to piece together the life and work of individual craftsmen.

This summer my wife and I had the opportunity to visit the Winterthur Museum and Gardens in Delaware and visit the Dominy Clock and Furniture Shop exhibit which was an exceptional window in the life of an 18th and 19th century family of craftsmen.

The Dominy’s were a family of craftsmen from Easthampton New York — out on the east end of Long Island, not terribly far from where I grew up in West Islip, NY. Over the course of four generations and active from ~1750-1850 this family produced fine clocks and furniture pieces that were sold locally and in regional markets. The surviving pieces are now prized by collectors.

Beyond the body of their work the shop is notable for how intact it is. The shop and it’s contents were cataloged and moved from Long Island in 1957 then reassembled and put on display at Winterthur starting in 1960.

The tools, benches, templates, partially completed pieces, log books and parts of the original shop building survived together.

It looks as if that last Dominy walked off the job and and could be expected to come back and resume work at any moment.

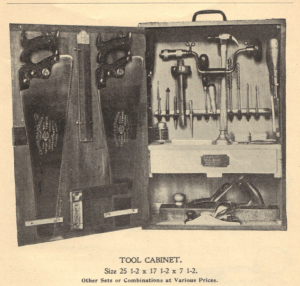

From the great wheel lathe, to the benches and shave-horse they had a sizable and well laid out shop for the time period. The tools were a mixture of locally made and imported tools.

I was fascinated by the tool marks, storage racks and modifications similar to things I’ve done in my own work.

In addition there is also the diminutive Clock Shop which is packed full of metal working tools needed to craft intricate gears and other clock component.

Written to go with the exhibit was Charles Hummel’s seminal book ‘With Hammer in Hand’ (1968). The book can be hard to find and on the pricey side as it has long since been out of print, but is worth every cent. I finally obtained a copy this spring as part of the EAIA’s annual fundraiser auction. The book explores the family, the tools, and the work they did in a way that was enjoyable to read. It paints a vivid picture of what life was like for these skilled craftsmen.

If you’d like to plan your own visit to see the Dominy exhibit you can learn more about it here.

If you’d like to visit on a budget, you can view some online video tours of the gallery below as Roy, Norm and even Bob Vila have segments about the shop.

Roy Underhill Visits the Dominy Shop (towards the end of this clip)

Norm Abram visits the shop and builds a replica clock at the New Yankee Workshop

and Bob Vila explores the shop

Take care,

-Bill