Woodworking is a lifelong journey of discovery and rediscovery. Along the way you’ll meet a lot of great folks and interesting characters who are surprisingly willing to share advice and help you out. The craft has been passed down this way for millenia.

Everything Old is New Again

Modern woodworking media seems to go in cycles much like clothing styles or car designs. Right now it’s popular to study the early works of Moxon, Roubo and Nicholson etc., or prove you have the best router or table saw trick. Others are interested in espousing the mix of old and new tools and techniques which is not a new concept. Manual training programs like those at NBSS have been doing it for over 125 years and the Shakers before them etc.

I want to buck the current trend and take a trip back to the 20th century. When I got started in traditional woodworking one of the first teachers I had was Tage Frid via the ‘Tage Frid Teaches Woodworking’ 3 volume set with its iconic white covers. I haven’t seen these books or Tage’s work come up much lately and thought it would be helpful to blow the dust off those books hopefully re-kindle some interest as I think they are a great resource.

Tage Frid

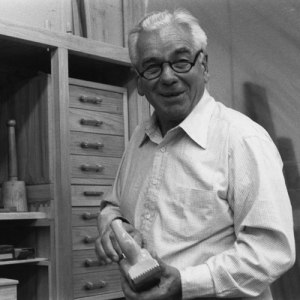

Tage (Pronounced ‘Tay’) taught me and countless other woodworkers the basics via his books and teaching. He grew up in Denmark and apprenticed as a cabinetmaker. His time as a journeyman took him to various other shops including the Royal Danish Cabinetmakers. In 1948, at the age of 33, the American Craft Council persuaded him to immigrate to New York and teach woodworking. Tage lead the woodworking program at the School for American Craftsman in Alfred NY which was later moved to the Rochester Institute for Technology. From 1962-1985 Tage was a professor of Woodworking and Furniture Design at RISD helping to propel that program to national prominence.

Also notable was Tage’s involvement with Fine Woodworking where he worked as an editor from it’s inception in 1975, through 171 issues until his passing in 2004. Described as having a sharp tongue and an ‘impish’ smile you can get a small taste it it through his writing and interviews which often have some memorable nuggets.

He could cut a dovetail while joking and flirting with the ladies. He referred to nails in furniture as ‘Swedish dowels.’ When critiquing a piece of work, which was nerve-wracking for students, the blow was slightly blunted by his sarcastic humor. Hank Gilpin recounts some memorable zingers:

“Oh, good curve. Too bad it’s the wrong one”

“Nice dovetails. What’d you use — a chainsaw?”

“Beautiful legs Henry. What were you thinking about — an elephant?”

And the classic: “Congratulations, you’ve just figured out the most complicated way to hold a board 30 inches off the floor.” [*]

The goal was not to put anyone down, it was to help each student stay humble and push him or herself to reach new heights in a fatherly kind of way. I had a similar experience during my own training and find myself rehashing some Frid one liners and Rich Friberg-isms in my own shop and classroom. Thankfully the flavor of sarcasm I learned from Rich is a little less harsh, but still fun.

Teaching

When asked about teaching repetitive topics Frid had the following to say:

Don’t you get bored demonstrating the same old dovetail?

“Maybe you left too early. I always demonstrate difficult joints and techniques depending on what the audience wants. The dovetail is just the overture. What I like about teaching is that I learn something new every day. A student asks me, ‘Why can’t I do it this way?’ and I think, ‘Why not?’ Then we figure it out.” — Tage Frid (excepted from an old interview in Fine Woodworking you can read here.)

Levity aside, Frid’s teachings focused on teaching solid joinery — form should follow function, wood has a beautify of its own that should be enhanced and not hidden and instilling an innate sense if proportion via a keen eye for detail.

“The best tool is the eye. Train the eye. The eye guides your hands to achieve the form. If the eye says ‘It’s right’, it is right” — Tage Frid [*]

With a solid grounding in the basics and exposure to a wide range of tools and techniques students are able to take on whatever challenge a project or shop can throw at them. During his lengthy career as a teacher, writer, editor and studio craftsman Frid helped teach several generations of woodworkers. You can see his work live on through his students and their students.

Design

Working in the Danish-modern style a lot of Frid’s pieces had a distinctive look compared to many of his American contemporaries. They were generally lighter looking with delicate lines and curves that celebrated the grain. The designs are especially interesting when you view them in the context of the time they were produced — the 1940s-1980s. Many of them were years ahead of what we think of as the the mainstream designs of the time .

For me, one of his most iconic pieces is the now famous 3 legged stool. If you read his 3rd book you’ll learn about how he came up with the design while watching a horse show and sitting on a fence. It was an interesting case study as he explains some of the revisions he went through to hone the design. These stools have been on my mental to-do list for about a decade now and I hope to eventually build some for myself.

When he first arrived in the US in the 1940s there were no good places to get a solid workbench. As a result Frid had to design and build a bench for himself and for his classrooms. Based on a traditional continental design with a shoulder vise and a tail vise the bench below was well suited for a cabinet maker. Over the years many a student, both in person and via his writing, would build and use one of these benches or a similar variant. In some upcoming posts you’ll see me build a scaled up version for my own shop.

What’s with the book report on Tage Frid?

Tage Frid’s work has shaped several aspects of my woodworking, design and teaching and I had a laundry list of odds and ends I wanted to share with you here. I also have been working to finish off my Tage Frid inspired bench and wanted to set the stage for it. And lastly because once I saw it, I could not un-see it — my Dad (who was my first woodworking instructor) is a bit of a doppelganger for Tage Frid. (Check out the picture below and compare it to the first picture of Tage Frid in this post) They both have very similar body shapes, taste in glasses, hairline and half smiles. I can’t talk too much because I look a lot like my Dad, I’m just the taller model at 6′-2″, so I suspect there will be a similar picture of me someday in the shop.

If you are interested to learn more about Tage Frid please check out the links below, it’s worth the time.

Other Tage Frid Resources:

- From Fine Woodworking Issue #1

Tage’s thoughts on the history of the chair, designers and craftsmen, good designs and joints of today will becomes classical furniture of the future - One on one with Tage Frid from FWW

- Oral history with Tage Frid from the Smithsonian

- A great first hand account of what life what like in Tage’s classroom from FWW and Hank Gilpin

- Tage Frid Teaches Woodworking Boxed Set + DVD

Time to get back out into the shop — it’s cold outside.

Take care,

-Bill

P.S. I never got to meet Tage Frid in person, he passed away while I was living out in Seattle but I would have loved to meet him. If anyone knew him personally I’d be curious to know a few things I haven’t been able to find online:

- What happened to his shop, bench and tools? Are they in a museum somewhere? Did they go to his grandson?

- Anyone have a picture of him in the classroom near the iconic benches he used to build?